Gentrify Your Own Hood: The Hussle Model as the Antidote to Gentrification?

What Community Development Looks Like, from the Inside Out

On the one-month anniversary of the death of Nipsey Hussle (born Ermias Asghedom), his work and activism has been recounted and mourned by thousands. Yet the part of his legacy that might be most missed, is the potential for his blueprint to transform urban neighborhoods – from the inside out.

On March 28th, 2019 news traveled across media outlets that Nipsey Hussle had been shot and killed in front of his Marathon store in the Hyde Park neighborhood of South Los Angeles. The hip-hop community, shocked fans, and countless others who merely knew of his music via his relationship with actress Lauren London were stunned. The couple had recently been featured in a GQ article as a 2019 Power Couple, and the streets were rooting for them.

Yet Hussle, who had been nominated for a Grammy-award for his music, was far from being a conventional rap artist. He has been described as a kind of community activist, philanthropist, and investor, turning his gang affiliation into a cautionary tale while putting his money behind investments in his community.

Partnering with music influencers and real estate developers, Nipsey opened a clothing store, barber shop, and fish market at the intersection of Slauson Avenue and Crenshaw Boulevard, the heart of his South LA neighborhood. He also partnered with investors to create a science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) after-school program, a co-working space, and several entrepreneurial projects to his neighborhood. The mall in which his stores were located would eventually include a mixed-use condo development that would house apartments for low-income families. Hussle was proud that he had literally “bought the block” and his vision included expanding those efforts to other cities around the country. As if that weren’t contribution enough, Nipsey was also involved in renovating playgrounds, basketball courts, skating rinks, and providing jobs and shelter for homeless residents. He had recently co-launched “Our Opportunity,” with friend and business partner, David Gross, in a coalition devoted specifically to developing properties and revamping the most dispossessed neighborhoods across the nation. The tool used to aid this development, Opportunity Zones, are somewhat controversial given their potential to be used primarily by large corporations for tax benefits. Yet Nipsey Hussle was doing what many urban planners and city officials aim to do. And he’s done it all without displacing long-time community residents. His popularity and appeal has only increased as a result of his involvement in multiple projects, and he’s positioned himself as working within his community to improve it, rather than bringing in capital for his own personal benefit or to replace existing neighborhood businesses.

Questions probing why a man with such great vision died as he was just reaching his prime often reference Nipsey’s character, his love for his community, and his determination not to give up on it. For many people who grew up in what has been labeled as “the inner city,” Nipsey’s story hits close to home.

In my research on gentrification and urban residents, I often hear older people lament that there are doctors, lawyers and entrepreneurs in the neighborhood, and that the youth just need a little guidance, a helping hand, or a way out. The fact that Nipsey opened a STEM center as a bridge between primarily lower-income kids from Crenshaw and Silicon Valley (and had plans to expand across three cities) shows that he both knew and embodied this wisdom. He opened the center, Vector 90, as a way to give young people more options and opportunities in life. In neighborhoods where disinvestment is high, routes to success are often severely limited and sometimes illegal. Hussle wears his experiences as a badge of honor, yet encourages those coming behind him to be different, think differently, and not to be afraid to pursue different paths, all while being proud of the neighborhood that raised them.

To be sure, Hussle was a visionary and a community leader. He was also what some might think of as the antidote to gentrification. Neighborhoods that have suffered from years of benign neglect and disinvestment are now gentrifying at breakneck speed. Neighborhoods are not only losing housing, but they are also losing people – the social resources that have always been the glue that has sustained close-knit ethnic minority communities. As foreign investors and major capital projects backed by nameless private investors infiltrate neighborhoods in cities across the country, Nipsey is seen as a hero – A Black man from the neighborhood, staying in his neighborhood, investing in that neighborhood, and partnering with others to help him build it into a large-scale community redevelopment project. He is often quoted as saying,

“In our culture, there’s a narrative that says, ‘Follow the athletes, follow the entertainers….that’s cool, but there should be something that says, ‘Follow Elon Musk, follow Zuckerberg.’ I think that with me being influential as an artist and young and coming from the inner city, it makes sense for me to be one of the people that’s waving that flag. (LA Times, 2018)”

For Nipsey – and countless other brown and black kids living in places that have written off – the notion of working collaboratively with others to improve your neighborhood is not just ‘a good thing’. Its empowering. It’s freedom. It feels good to have people who look like you, who’ve grown up in the same neighborhood as you saying, ‘C’mon, let’s do something good here’. This, not gentrification, is the model communities have been asking for. It’s what they deserve.

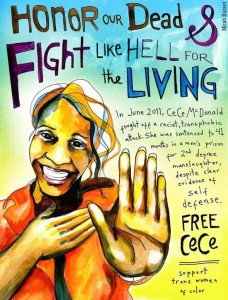

Did you know that homicide is the second leading cause of death for Black women aged 20-24? The truth is that for some Black women, they feel as though they are surviving day-to-day instead of living.

Did you know that homicide is the second leading cause of death for Black women aged 20-24? The truth is that for some Black women, they feel as though they are surviving day-to-day instead of living.

While shedding some light on the complicated nature of disclosure and IPV, these claims only scratch the surface. Black women who don’t report IPV are often in the position of protecting their families, partners and children while averting the reality of abuse. Regardless of the rationale, the fact that partner abuse is a life-altering experience is a truism. The long-reaching effects can be traumatic for the women and their families; in some cases, cycles of violence are reproduced over generations. Victims of IPV often experience guilt, anxiety, phobias, substance and alcohol abuse, sleep issues, alienation, aggression and sexual dysfunction. They are three times more likely to suffer from depression and six times more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder.

While shedding some light on the complicated nature of disclosure and IPV, these claims only scratch the surface. Black women who don’t report IPV are often in the position of protecting their families, partners and children while averting the reality of abuse. Regardless of the rationale, the fact that partner abuse is a life-altering experience is a truism. The long-reaching effects can be traumatic for the women and their families; in some cases, cycles of violence are reproduced over generations. Victims of IPV often experience guilt, anxiety, phobias, substance and alcohol abuse, sleep issues, alienation, aggression and sexual dysfunction. They are three times more likely to suffer from depression and six times more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder.