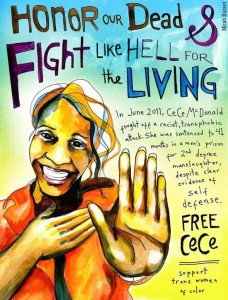

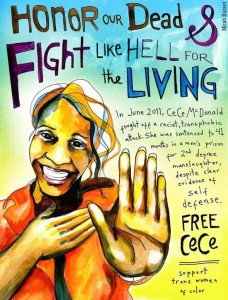

I recently posted a link for Free CeCe (a documentary-in-progress by Laverne Cox and CeCe McDonald) to a listserv of friends and colleagues. CeCe McDonald is a Black transgender woman and activist. She was sentenced to 41 months in a male prison for stabbing a man who attacked CeCe and her friends in Minneapolis, Minnesota. CeCe’s case generated a significant amount of media attention and public discussion surrounding the victimization and harassment suffered by trans-women and particularly trans-women of color (WOC). Cece was released from prison in January 2014 after serving 19 months, and in her subsequent media appearances CeCe used her platform to discuss her life experiences as a trans-woman, her prison sentence and regaining her life.

I recently posted a link for Free CeCe (a documentary-in-progress by Laverne Cox and CeCe McDonald) to a listserv of friends and colleagues. CeCe McDonald is a Black transgender woman and activist. She was sentenced to 41 months in a male prison for stabbing a man who attacked CeCe and her friends in Minneapolis, Minnesota. CeCe’s case generated a significant amount of media attention and public discussion surrounding the victimization and harassment suffered by trans-women and particularly trans-women of color (WOC). Cece was released from prison in January 2014 after serving 19 months, and in her subsequent media appearances CeCe used her platform to discuss her life experiences as a trans-woman, her prison sentence and regaining her life.

In my e-mail post, I solicited opinions about CeCe. I was curious what a group of college-educated, middle class, African American thirty-something professionals thought about CeCe’s (and other trans-WOC) experiences that often entail violence and abuse? How do we think about the voices of Black LGBT*Q folks at the intersection? Where do we place sexuality in the politics of antiracism efforts? And how do we teach our peers and children about acceptance and the importance of being allies?

Good questions, right? I thought so too. Until a day, then 2 days passed. No response. A week. Still no response. The silence was deafening. A group of very knowledgeable people who definitely had opinions on a wide range of issues and not one. single. comment. about my post? Surprised and outraged, I followed up. “What gives? Why the silence?”

Then, someone offered this:

“For most people, until they know someone, until it affects them directly, or until it is right in their own back yard do people rarely care (or pay attention to) specific issues. Until then, it’s just an abstract thought that you may be aware of but not really motivated to do anything about.

It’s even more a problem in the Black community since we tend to suppress/ignore issues even when they do affect us (dietary behaviors, depression, sexual assault, sexuality, etc.). AND because we (compared to other groups) strongly stick to a religious dogma that teaches us to blindly accept/ignore things and to pray away our “problems” instead of talking about them.

The key is having an open dialogue on all of these things which, in a way, makes the world smaller and makes relating to people/issues easier even if not directly affected. I think younger generations growing up with social media exposes them to topics that older generations (all of us included) didn’t have access to.”

Finally.

However, as on-point as the comment was, I still had questions. Are we now part of an “older generation” that is too set in traditional ways of thinking to grapple with these issues? Is not knowing an excuse for not caring? How can we begin to engage in difficult dialogues, and more importantly solutions, if we remain SILENT? I wondered what the other 99% of the listserv thought? Did they agree and if so, why didn’t they speak up? Again, why are we so SILENT?

However, as on-point as the comment was, I still had questions. Are we now part of an “older generation” that is too set in traditional ways of thinking to grapple with these issues? Is not knowing an excuse for not caring? How can we begin to engage in difficult dialogues, and more importantly solutions, if we remain SILENT? I wondered what the other 99% of the listserv thought? Did they agree and if so, why didn’t they speak up? Again, why are we so SILENT?

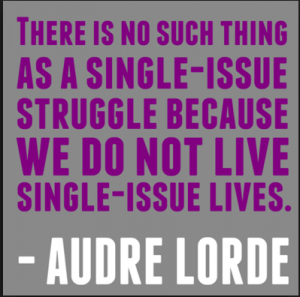

As I consider my own research dealing with the complicated nature of intersectionality, I can’t help but notice that everyone has not come to join my party at the crossroads. In fact, many people don’t consider their identities (much less the identities of others) as intersectional. It was a sobering moment. A moment that makes me realize that beyond the academic labor, there is real work to be done on the ground in raising the consciousness of people living ‘at the intersection’ and outside of it. For instance, there is real work to help our brothers understand how to work together in helping to empower, not objectify and destroy, Black women. There is real work in getting the word out that (black) feminism is not a dirty word and yes, men, you too can join the movement. And, there is real work in paying attention to – and understanding the experiences of – the CeCe’s of the world.

The list continues to grow.

If Crenshaw really did conceptualize the term intersectionality from a schema of intersecting roadways, then it stands to reason that in all of its complexity, some people will be left in the median wondering where they fit (if at all). Isn’t it time we did something to translate and disseminate the message of what it means to be a true ally – and to “do intersectionality” – far and wide? While we debate the future of intersectionality, with the conceptual and measurement issues on one front, we also need to coordinate ways to do the work required to reach everywoman/man.

Carbado et al. (2013) explain:

“When Kimberlé Crenshaw drew upon Black feminist multiplicitous conceptions of power and identity as the analytic lens for intersectionality, she used it to demonstrate the limitations of the single-axis frameworks that dominated antidiscrimination regimes and antiracist and feminist discourses. Yet…the goal was not simply to understand social relations of power, but to bring the often hidden dynamics forward in order to transform them. Understood in this way, intersectionality, like Critical Race Theory more generally, is a concept animated by the imperative of social change.”

As we see, the very essence of intersectionality is historically steeped in centering perspectives as a tool of analytical, theoretical and social development. Our potential to be transformative depends on facilitating efforts to change structural invisibility and inequality. So what are we waiting for? Let’s get on with it.

Did you know that homicide is the second leading cause of death for Black women aged 20-24? The truth is that for some Black women, they feel as though they are surviving day-to-day instead of living.

Did you know that homicide is the second leading cause of death for Black women aged 20-24? The truth is that for some Black women, they feel as though they are surviving day-to-day instead of living.

While shedding some light on the complicated nature of disclosure and IPV, these claims only scratch the surface. Black women who don’t report IPV are often in the position of protecting their families, partners and children while averting the reality of abuse. Regardless of the rationale, the fact that partner abuse is a life-altering experience is a truism. The long-reaching effects can be traumatic for the women and their families; in some cases, cycles of violence are reproduced over generations. Victims of IPV often experience guilt, anxiety, phobias, substance and alcohol abuse, sleep issues, alienation, aggression and sexual dysfunction. They are three times more likely to suffer from depression and six times more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder.

While shedding some light on the complicated nature of disclosure and IPV, these claims only scratch the surface. Black women who don’t report IPV are often in the position of protecting their families, partners and children while averting the reality of abuse. Regardless of the rationale, the fact that partner abuse is a life-altering experience is a truism. The long-reaching effects can be traumatic for the women and their families; in some cases, cycles of violence are reproduced over generations. Victims of IPV often experience guilt, anxiety, phobias, substance and alcohol abuse, sleep issues, alienation, aggression and sexual dysfunction. They are three times more likely to suffer from depression and six times more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder.