As we enter into the third quarter of 2014, it seems like a good time to review the changes enacted by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and what good/bad impacts these changes have had for women’s health and underserved groups. It’s a larger discussion than to be had here for sure, but engaging in the conversation is important in ensuring that we continue to push for not only accessibility, but equity in health care as well.

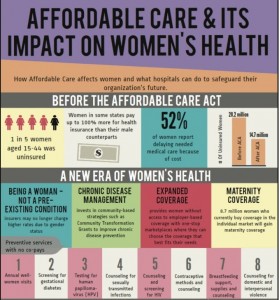

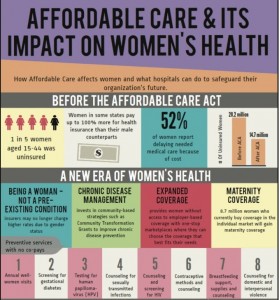

The passing of the ACA signals a significant advancement in women’s health and public policy in general, ensuring that millions of women now have access to affordable health coverage. Women no longer pay more than men just for being women (e.g., gender rating). Unbelievably, for the first time in history – this overt gender discrimination is now prohibited in federally funded health care. Women will also not be denied coverage for pre-existing conditions, such as a Caesarean section or having received medical treatment for domestic violence. Lifetime dollar-value caps are no more, maternity coverage is now considered an essential health benefit and preventive services have been expanded to include contraceptives, mammograms and cervical cancer screenings with no deductibles or co-pays. Although the contraceptive mandate has stirred controversy in public discourse, the fact that birth control is available on both public insurance and private plans without out-of-pockets costs represents progress. Employers (non-religious) are not only required to provide birth control as part of insurance plans offered to employees, companies must also – and this is a big one for anyone who has ever breastfed – offer hourly employees a clean, safe space in which to pump (e.g., not an office closet or restroom).

The passing of the ACA signals a significant advancement in women’s health and public policy in general, ensuring that millions of women now have access to affordable health coverage. Women no longer pay more than men just for being women (e.g., gender rating). Unbelievably, for the first time in history – this overt gender discrimination is now prohibited in federally funded health care. Women will also not be denied coverage for pre-existing conditions, such as a Caesarean section or having received medical treatment for domestic violence. Lifetime dollar-value caps are no more, maternity coverage is now considered an essential health benefit and preventive services have been expanded to include contraceptives, mammograms and cervical cancer screenings with no deductibles or co-pays. Although the contraceptive mandate has stirred controversy in public discourse, the fact that birth control is available on both public insurance and private plans without out-of-pockets costs represents progress. Employers (non-religious) are not only required to provide birth control as part of insurance plans offered to employees, companies must also – and this is a big one for anyone who has ever breastfed – offer hourly employees a clean, safe space in which to pump (e.g., not an office closet or restroom).

And what about older women? One of our fastest growing demographics? They benefit too through a host of programs to support caregivers (typically women). Dual-eligibles will also maintain a more integrated balance between Medicare/Medicaid and will be able cover more prescription drug costs.

With these benefits, its hard to imagine that the ACA is anything but a resounding success. Still, coverage gaps remain. Of the currently uninsured, approximately 20% are women. Furthermore, the failure of some states to expand Medicaid eligibility benefits will undoubtedly affect women’s health in profound ways. All in all, the report card is not yet conclusive as to whether individual mandates and state expansions fully address the needs of women in this country. There is a sizable proportion of women who will be excluded from receiving any benefits due to immigration status or costs associated with buying insurance on the individual marketplace.

Many women fall between a space where they fail to meet eligibility criteria for Medicaid and can’t afford to purchase private insurance on the exchange, even with tax credits and subsidies. And while primary care at federally qualified health centers is available, access and quality depend on geographic location. Its possible for women with limited options to continue to receive clinic and inpatient care at the remaining public hospitals and some non-profit hospitals that provide charity care, yet this is far from ideal and free clinics are few and far between. In addition to that, abortion is still not federally supported and accessibility and affordability varies on the health exchange. Drug coverage continues to be a priced at a premium and even though certain medications are subsidized by pharmaceutical companies, ultimately, mandating insurance coverage for the poor and underserved – many of whom are struggling to meet ends – is a difficult imperative. Ironically enough, the two ways in which the ACA was close to gaps – provide access and expanded benefits (at reduced cost) – are precisely the areas in which the most marginalized still find themselves lacking, with Medicaid expansions in many states (26) at a standstill.

Many women fall between a space where they fail to meet eligibility criteria for Medicaid and can’t afford to purchase private insurance on the exchange, even with tax credits and subsidies. And while primary care at federally qualified health centers is available, access and quality depend on geographic location. Its possible for women with limited options to continue to receive clinic and inpatient care at the remaining public hospitals and some non-profit hospitals that provide charity care, yet this is far from ideal and free clinics are few and far between. In addition to that, abortion is still not federally supported and accessibility and affordability varies on the health exchange. Drug coverage continues to be a priced at a premium and even though certain medications are subsidized by pharmaceutical companies, ultimately, mandating insurance coverage for the poor and underserved – many of whom are struggling to meet ends – is a difficult imperative. Ironically enough, the two ways in which the ACA was close to gaps – provide access and expanded benefits (at reduced cost) – are precisely the areas in which the most marginalized still find themselves lacking, with Medicaid expansions in many states (26) at a standstill.

Of course, its not simple to overhaul a national system that historically, was never intended to provide universal access to care. And the ACA shouldn’t be blamed for the complicated and dysfunctional system it took centuries to create. Some parts of the ACA are working; but others still need tweaking. For those of us working in the community and serving underserved populations, its important to not only understand these shortcomings, but also to advocate on behalf of women, children and the un(under)insured who may be navigating a complicated system or shut out altogether.