Disrupting Hair Habitus

Could “hair habitus” be a thing? Or as one reviewer suggested, “acceptable presentation habitus”? In any case, I’m curious how hair intersects with the concept of habitus and health intervention research. Habitus originates from Bourdieu (1977), in which he argues that certain mundane acts are an elaborate performance. What do we perform, you ask? Well, there’s no short answer because there are a myriad of ways we perform gender, social class and identity every day. In essence, habitus refers to implicit practices and routines that structure the logic of everyday life.

Could “hair habitus” be a thing? Or as one reviewer suggested, “acceptable presentation habitus”? In any case, I’m curious how hair intersects with the concept of habitus and health intervention research. Habitus originates from Bourdieu (1977), in which he argues that certain mundane acts are an elaborate performance. What do we perform, you ask? Well, there’s no short answer because there are a myriad of ways we perform gender, social class and identity every day. In essence, habitus refers to implicit practices and routines that structure the logic of everyday life.

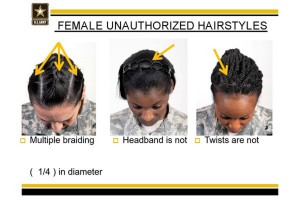

In this way, I think about how Black women’s relationships to hair are formed differently across class lines. Perhaps the primary question is, are they? Are attachments to hair and specifically hairstyle, more salient for certain class groups? Of course, these theoretical musings are not simply rhetorical questions. They matter in the sense of understanding and breaking cycles involving health, class and the racialized gendered body. From my standpoint, hairstyling and daily grooming is a significant daily performance. For Black women in particular, our hair conveys messages to the world about who we are and how we want to be seen. Yet I struggle in articulating a theory that expresses the way in which hair is in conversation with our bodies and our health. How do we meaningfully incorporate ideals of beauty, femininity, hair and health?

A second tenet is that habitus is shaped by social and economic conditions. Perhaps one primary strategy for transforming the dissonance between *some* Black women who struggle with maintaining hair and a daily exercise practice, for example, includes disrupting habitus. According to Bourdieu, mundane acts of everyday life can be restructured to accommodate new interests and practices. So for example, if we encourage women to exercise at work, then we must design interventions that focus on the challenges associated with integrating workplace-exercise with daily grooming practices. We must purposefully restructure our routine in a way that successfully incorporates physical activity. Exercise interventions cannot be disconnected from the sociocultural contexts in which we live. By providing models that integrate structure and “real world” application, we are able to design culturally appropriate ways to meet the needs of women’s health.

A second tenet is that habitus is shaped by social and economic conditions. Perhaps one primary strategy for transforming the dissonance between *some* Black women who struggle with maintaining hair and a daily exercise practice, for example, includes disrupting habitus. According to Bourdieu, mundane acts of everyday life can be restructured to accommodate new interests and practices. So for example, if we encourage women to exercise at work, then we must design interventions that focus on the challenges associated with integrating workplace-exercise with daily grooming practices. We must purposefully restructure our routine in a way that successfully incorporates physical activity. Exercise interventions cannot be disconnected from the sociocultural contexts in which we live. By providing models that integrate structure and “real world” application, we are able to design culturally appropriate ways to meet the needs of women’s health.

As public health professionals, it is imperative to acknowledge, not discount, the reality that hair management for some women is a barrier to exercise. In moving forward, our aims should include disrupting the notion that one cannot both preserve hairstyles while exercising. To do so requires identifying strategies that incorporate flexible planning and social support into intervention research.

As public health professionals, it is imperative to acknowledge, not discount, the reality that hair management for some women is a barrier to exercise. In moving forward, our aims should include disrupting the notion that one cannot both preserve hairstyles while exercising. To do so requires identifying strategies that incorporate flexible planning and social support into intervention research.