Are Black women at risk? Part II: Black Women Face Greater Risk of Exposure to Violence

Did you know that homicide is the second leading cause of death for Black women aged 20-24? The truth is that for some Black women, they feel as though they are surviving day-to-day instead of living.

Did you know that homicide is the second leading cause of death for Black women aged 20-24? The truth is that for some Black women, they feel as though they are surviving day-to-day instead of living.

“To face the realities of our lives is not a reason for despair—despair is a tool of your enemies. Facing the realities of our lives gives us motivation for action. For you are not powerless… You know why the hard questions must be asked. It is not altruism, it is self-preservation—survival.”

– Audre Lorde (1989), Oberlin College Commencement Address

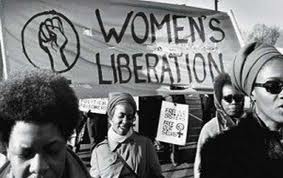

We might better understand the reason behind this sentiment considering the statistics facing Black women and the exposure to violence. Black women are especially likely to be a victim of violence in America. The fact that no woman is more likely to be raped in America today than a Black woman is sobering. Black women are more than three times as likely to be murdered as are white women and are in fact, the most likely group of women in America to become a victim of homicide. Though only approximately 8% of the population, Black women comprise 29% of women who experience intimate partner violence (IPV). Yet Black women are less likely than other groups to utilize social services, such as battered women’s programs. These statistics represent a cry for action to expand public health research and public policy to reconsider protections afforded Black women.

Unfortunately, young Black girls face similar challenges in navigating environments marked by violence and peril. Black adolescent girls are disproportionately impacted by zero tolerance school policies, and experience an increased risk of becoming involved in the criminal justice system at some point during elementary school education. #BlackGirlsMatter!

Reports also reveal that nearly 60 percent of Black girls are abused by an intimate partner before reaching the age of 18. Yet, Black women are less likely to go to the police or file a report against their attacker. Why? While complicated, we may be able to understand this paradox in the cultural and political context of systematic racism, fear and distrust in official authorities. Reports claim that Black women have the “tendency to withstand abuse, subordinate feelings and concerns with safety, and make a conscious self-sacrifice for what she perceives as the greater good of the community, but to her own physical, psychological and spiritual detriment.” (Bent-Goodley, 2001)

While shedding some light on the complicated nature of disclosure and IPV, these claims only scratch the surface. Black women who don’t report IPV are often in the position of protecting their families, partners and children while averting the reality of abuse. Regardless of the rationale, the fact that partner abuse is a life-altering experience is a truism. The long-reaching effects can be traumatic for the women and their families; in some cases, cycles of violence are reproduced over generations. Victims of IPV often experience guilt, anxiety, phobias, substance and alcohol abuse, sleep issues, alienation, aggression and sexual dysfunction. They are three times more likely to suffer from depression and six times more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder.

While shedding some light on the complicated nature of disclosure and IPV, these claims only scratch the surface. Black women who don’t report IPV are often in the position of protecting their families, partners and children while averting the reality of abuse. Regardless of the rationale, the fact that partner abuse is a life-altering experience is a truism. The long-reaching effects can be traumatic for the women and their families; in some cases, cycles of violence are reproduced over generations. Victims of IPV often experience guilt, anxiety, phobias, substance and alcohol abuse, sleep issues, alienation, aggression and sexual dysfunction. They are three times more likely to suffer from depression and six times more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder.

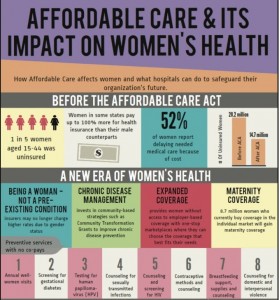

Isn’t it time that we sound the alarm that domestic violence is a national priority for Black women’s health?