“What exactly is generativity?”

“What exactly is generativity?”

If I had a nickel for every time I’ve encountered this question.

On the surface, generativity might seem no more than one stage of a psychological theory conceived to describe lifespan development. In reality, it defies this simplistic description. We spend the bulk of our adult lives in midlife. Midlife boundaries keep changing, but it loosely refers to the period between 30 – 60 years of age. Thus, generativity characterizes that fuzzy time between early adulthood and older age, and holds tremendous promise for linking psychosocial development to health, productivity and aging. Erikson argues that generativity, or the desire to create things that outlast the self (e.g., parenting, leaving a legacy, teaching, philanthropy), are hallmarks of midlife.

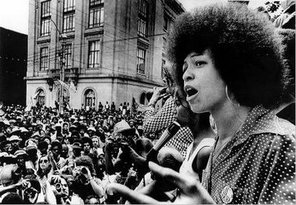

By integrating the Eriksonian notion of lifespan development with theories of social engagement, we learn that there are differential motivations for engaging in one’s community. We also learn that people often feel generative well-beyond midlife and express generativity in variant ways. For example, in a study of Black and White educated women in late midlife, paid work plays a central role in Black women’s lives at midlife, whereas for White women, spirituality becomes more important. Of course, most Black women don’t increase in spirituality/religiosity during this time, as engagement with the church is a continued commitment over the lifespan. It is not only where spiritual nourishment is received, but it continues to be the site of community engagement and activism for Black women. Slevin (2005) notes that the transition between midlife and retirement is viewed by Black women as free time to devote to church and community work, not necessary leisure activity. One woman recounts,

By integrating the Eriksonian notion of lifespan development with theories of social engagement, we learn that there are differential motivations for engaging in one’s community. We also learn that people often feel generative well-beyond midlife and express generativity in variant ways. For example, in a study of Black and White educated women in late midlife, paid work plays a central role in Black women’s lives at midlife, whereas for White women, spirituality becomes more important. Of course, most Black women don’t increase in spirituality/religiosity during this time, as engagement with the church is a continued commitment over the lifespan. It is not only where spiritual nourishment is received, but it continues to be the site of community engagement and activism for Black women. Slevin (2005) notes that the transition between midlife and retirement is viewed by Black women as free time to devote to church and community work, not necessary leisure activity. One woman recounts,

“Being retired means for me being of service and I don’t have time for anything that’s not going

to make a difference in this community. Okay? So, that’s it in a nutshell: being of service and

helping out.”

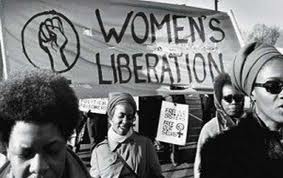

Black women’s work as agents of social and community change has a long history. In many respects, Black women bunk the model that midlife defines a particularly generative moment. Black women have historically been integrally connected to their communities and generativity is therefore normative, if not expected.

Returning to the original question regarding the importance of generativity, it is necessary to extend the narrative of generativity beyond Erikson. Essentially, generativity is more than one component of psychological theory, it has practical application. There are generative contributions being made in ethnic-minority communities that build generative families and social capital. Within the social sciences there is a significant body of literature on volunteerism and pro-social participation, yet there is almost no mention of volunteerism and social participation among ethnic minorities. Therefore, acknowledging these normative expressions (and documenting them) allows for re-centering the conversation to highlight the human resources that make our communities strong and resilient, rather than “inner city”, “distressed” or “marginalized”.

Returning to the original question regarding the importance of generativity, it is necessary to extend the narrative of generativity beyond Erikson. Essentially, generativity is more than one component of psychological theory, it has practical application. There are generative contributions being made in ethnic-minority communities that build generative families and social capital. Within the social sciences there is a significant body of literature on volunteerism and pro-social participation, yet there is almost no mention of volunteerism and social participation among ethnic minorities. Therefore, acknowledging these normative expressions (and documenting them) allows for re-centering the conversation to highlight the human resources that make our communities strong and resilient, rather than “inner city”, “distressed” or “marginalized”.

Generative acts should not be limited to volunteering or philanthropic gestures of the elite. Rather, our communities thrive on “giving back” and paying-it-forward actions that are a part of the everyday fabric. Another woman from Slevin’s study notes:

“If we achieve something, we have to give something back. We’ve always known that. Everybody

black knows that. That’s why you hear the basketball players and the football players that are

making such a wad of money, always doing something, establishing some sort of foundation or

working with the ghetto kids or doing something. Because they know that they have got to give

something back. That’s just. . .the creed in the black community.”

In fact, our own research shows that compared to educated Black women, educated White women need to feel generative in order to act generative. Whereas, Black women behave in such a way regardless of psychological motivations. This illustrates a central point. The relational aspects of our communities are deeply nuanced and intersectional. Uncovering the links between social identity, altruism/generativity and community engagement have the potential to be transformative. Since social processes have been postulated to “get under the skin”, isn’t it about time that we give serious attention to social capital, its antecedents and how community agents use generative elements to strengthen social ties?

In fact, our own research shows that compared to educated Black women, educated White women need to feel generative in order to act generative. Whereas, Black women behave in such a way regardless of psychological motivations. This illustrates a central point. The relational aspects of our communities are deeply nuanced and intersectional. Uncovering the links between social identity, altruism/generativity and community engagement have the potential to be transformative. Since social processes have been postulated to “get under the skin”, isn’t it about time that we give serious attention to social capital, its antecedents and how community agents use generative elements to strengthen social ties?

Published by